Why are there differences between reported and estimated cases of smallpox?

Historical cases of smallpox were underreported to authorities. What was the extent of underreporting, and how do researchers adjust for this?

The global decline of smallpox

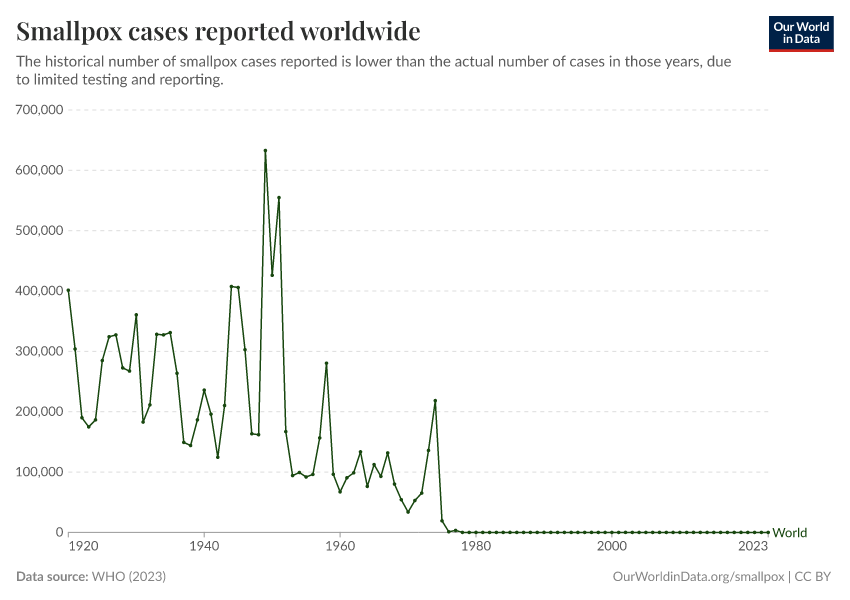

Global data on the number of smallpox cases is shown in the chart. Shown here is the number of reported smallpox cases worldwide from 1920 until the last case in 1977.

The reported number of smallpox cases between 1920 and 1978 amounted to 11.6 million cases – but that number was certainly smaller than the actual number of cases, although we do not know by how much.

Even though smallpox was easily visible and should therefore be relatively easy to document, there was not an international organization dedicated to collating this data before then, which means the number of reported cases could be substantially lower than the actual number of cases.

Crosby (1993) estimates that in 1967, 10–15 million people were still being infected with smallpox every year. In contrast, the chart on the reported cases below indicates only 132,000 for that same year.1

Why are there differences between reported and estimated cases?

Three main reasons are responsible for the huge differences between reported and the estimated (thought to be closer to the truth) number of cases and deaths due to smallpox.

First, many infections and deaths were not recorded simply because the monitoring public health system was dysfunctional and that was predominantly the case in developing countries where the disease burden was highest. Fenner et al. (1988) write: "It is clear that the reporting of cases of smallpox was the most efficient in countries in which the health services were well developed, which was usually where the disease was least common. It was very inefficient elsewhere."2

Second, classifying deaths posed another challenge. For instance if smallpox patients had already been suffering from pneumonia or even just a flu when becoming infected with smallpox and then died, it is unclear whether smallpox or pneumonia or the flu were the cause of death. Had a patient survived the smallpox infection if (s)he had not already been weakened by another disease, this creates a major challenge in classifying the cause of deaths which is likely to have further diminished the number of smallpox cases and deaths actually reported and recorded.

Third, some anecdotes suggest that some smallpox outbreaks were deliberately kept secret.3

Razzell (1977) writes in his book about British market towns: "Many tradesmen in market towns may have suppressed information about smallpox in their families and certainly the townspeople as a whole were very anxious to avoid advertising the presence of smallpox in their own town so as to avoid frightening country people from the surrounding area - there are many examples of markets being ruined for more than a year because of the presence of smallpox."4

Extent of reporting discrepancy

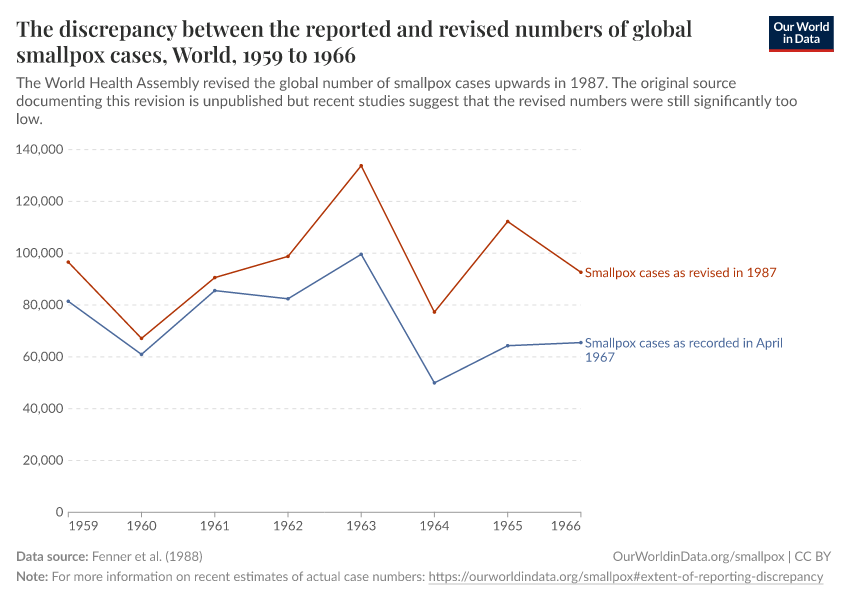

The World Health Assembly was aware of the underreporting and therefore attempted to correct the number of reported smallpox cases upward for the years 1959 to 1966, just before the Intensified Smallpox Eradication Program was launched.

The chart illustrates that the corrections were highest for 1965, where the originally reported smallpox cases only amounted to 64,000 cases which was corrected to almost double its value, 112,000 cases.

Many sources suggest, however, that even these corrections were small in comparison to what the actual extent of smallpox's disease burden was. Fenner et al. (1988) write "it is not unreasonable to regard the official figures reported to WHO as representing only 1–2 percent of the true incidence – probably nearer 1 percent for the years before the initiation of the global eradication programme. In the early 1950s, 150 years after the introduction of vaccination, there were probably some 50 million cases of smallpox in the world each year, a figure which had fallen to perhaps 10–15 million by 1967."2

These figures are also mentioned in the final report by the WHO that confirmed smallpox's eradication, along with the disease still causing approximately 2 million deaths in 1967.5

Henderson (1976) adds that the global case numbers reported to the WHO in 1967 probably were the number of infections taking place in northern Nigeria alone.6

In 1973, the World Health Organization conducted a thorough search for smallpox cases in line with its ring vaccination strategy in India: in a state that had reported approximately 500 cases a week, the search team found 10,000 cases.7

Endnotes

Crosby, A.W. (1993). Smallpox. In K.F. Kiple, The Cambridge World History of Human Disease (pp. 1008-1014). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Page 175 of Fenner, F., Henderson, D., Arita, I., Jezek, Z., & Ladnyi, I. (1988). Smallpox and its eradication. Geneva: World Health Organization. Fully available for download here.

"Statistics from India also showed deliberate distortion; at successive levels of the health hierarchy, statistics on smallpox incidence were modified to lower the number of cases reported up the line." Hopkins, J. (1989). The Eradication Of Smallpox: Organizational Learning And Innovation In International Health. Avalon Publishing.

Razzell, P. (1977). The Conquest of Smallpox: The Impact of Inoculation on Smallpox Mortality in Eighteenth Century Britain. Firle: Caliban Books.

World Health Organization (1980) The Eradication of Smallpox. Final Report of the Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication. Geneva. Fully available online on the WHO website.

Henderson, D. A. (1976). The eradication of smallpox. Scientific American, 235(4), 25-33. Available online through JSTOR.

World Health Organization (2008) Smallpox: dispelling the myths. An interview with Donald Henderson. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86(12). 909-988. Fully available online on the WHO website.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Sophie Ochmann and Max Roser (2018) - “Why are there differences between reported and estimated cases of smallpox?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/why-are-there-differences-between-reported-and-estimated-cases-of-smallpox' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-why-are-there-differences-between-reported-and-estimated-cases-of-smallpox,

author = {Sophie Ochmann and Max Roser},

title = {Why are there differences between reported and estimated cases of smallpox?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2018},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/why-are-there-differences-between-reported-and-estimated-cases-of-smallpox}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.