“Cool” years are now hotter than the “warm” years of the past: tracking global temperatures through El Niño and La Niña

The world is warming despite natural fluctuations from the El Niño cycle.

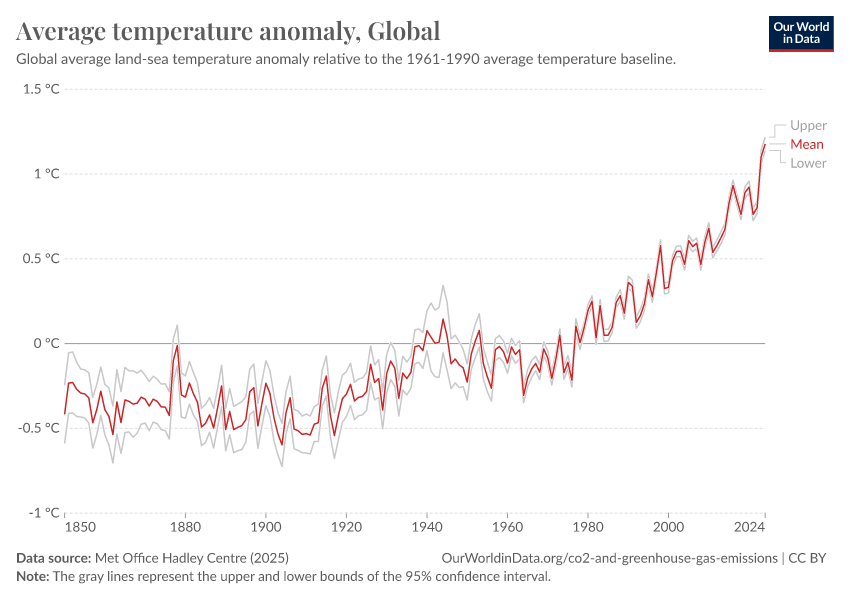

In 2024, the world was around 1.5°C warmer than it was in pre-industrial times.1 You can see this in the chart below, which shows average warming relative to average temperatures from 1861 to 1890.2

Temperatures, as defined by “climate”, are based on temperatures over longer periods of time — typically 20-to-30-year averages — rather than single-year data points. But even when based on longer-term averages, the world has still warmed by around 1.3°C.3

But you’ll also notice, in the chart, that temperatures haven’t increased linearly. There are spikes and dips along the long-run trend.

Many of these short-term fluctuations are caused by “ENSO” — the El Niño-Southern Oscillation — a natural climate cycle caused by changes in wind patterns and sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean.

While it’s caused by patterns in the Pacific Ocean and most strongly affects countries in the tropics, it also impacts global temperatures and climate.

There are two key phases of this cycle: the La Niña phase, which tends to cause cooler global temperatures, and the El Niño phase, which brings hotter conditions. The world cycles between El Niño and La Niña phases every two to seven years.4 There are also “neutral” periods between these phases where the world is not in either extreme.

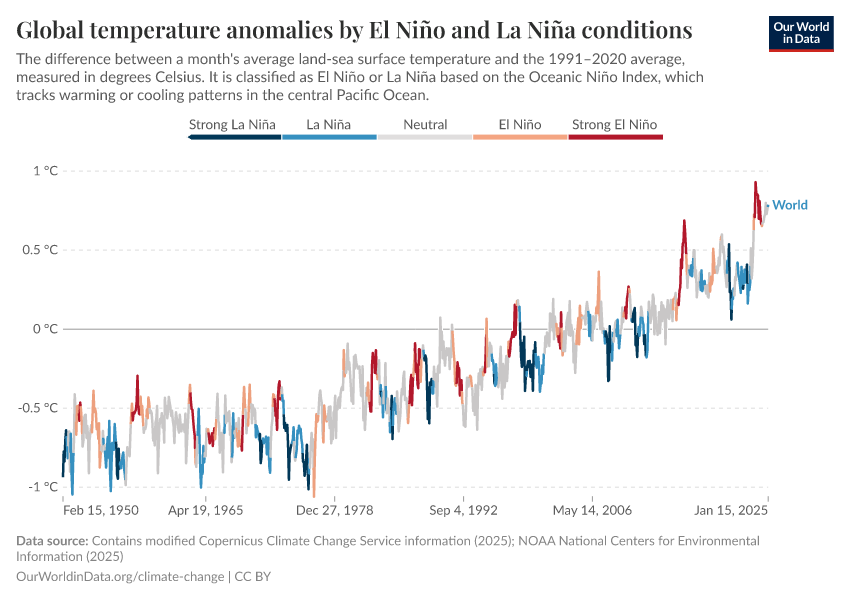

The zig-zag trend of global temperatures becomes understandable when you are taking the phases of the ENSO cycles into account. In the chart below, we see the data on global temperatures5, but the line is now colored by the ENSO phase at that time.6

The El Niño (warm phase) is shown in orange and red, and the La Niña (cold phase) is shown in blue.

You can see that temperatures often reach a short-term peak during warm El Niño years before falling back slightly as the world moves into La Niña years, shown in blue.

What’s striking is that global temperatures during recent La Niña years were warmer than El Niño years just a few decades before. “Cold years” today are hotter than “hot years” not too long ago.7

Continue reading on Our World in Data

Climate Change

How are global temperatures changing, and what are the impacts on sea level rise, sea ice, and ice sheets?

How much have temperatures risen in countries across the world?

Explore country-by-country data on monthly temperature anomalies.

More people care about climate change than you think

The majority of people in every country support action on climate, but the public consistently underestimates this share.

Endnotes

This was based on the annual average temperature anomaly, measured relative to 1850 to 1900 temperatures.

Note that the original dataset, HadCRUT5 — published by the Met Office Hadley Centre used average temperatures from 1960 to 1990 as the baseline. To make the total warming relative to pre-industrial times clearer, we have adapted this to make the baseline the average from 1861 to 1890.

For more context on how much the world has warmed — and how this relates to the 1.5°C target, see this article by Richard Betts and colleagues.

Betts, R. A., Belcher, S. E., Hermanson, L., Klein Tank, A., Lowe, J. A., Jones, C. D., ... & Stott, P. A. (2023). Approaching 1.5° C: how will we know we’ve reached this crucial warming mark?. Nature.

The exact length and intensity of these cycles are not always consistent but tend to be in that range.

To allow people to track monthly temperature changes, we use temperature anomalies from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 project. Since satellite data are available only from the 1950s, constructing an 1861–1890 baseline isn’t feasible. Instead, we use a 1991–2020 baseline, which is the standard reference period employed by our data source. Despite this change, the chart still shows a clear warming trend.

We’ve categorized this based on the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI), published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The ONI is used to monitor and track the presence and intensity of El Niño and La Niña events. It measures deviations in sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in a specific area of the Pacific Ocean, known as the Niño 3.4 region. We’ve used a classification based on the 3-month running mean of sea temperature anomalies.

For those keeping track of temperature changes on a monthly basis, we provide a chart that details this data by month. Using the same color categories as before, this chart shows the global temperature anomalies for each individual month.

You can see that typically, months in La Niña conditions are cooler than the same month in the preceding year during El Niño conditions. The red dots (indicating El Niño) usually sit above the preceding blue ones (La Niña). Nonetheless, January 2025 was the hottest January on record, surpassing January 2024’s El Niño temperatures even as the world transitioned into a colder La Niña phase.

Again, we will keep this updated monthly so you can track these temperature changes over time.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Veronika Samborska and Hannah Ritchie (2025) - ““Cool” years are now hotter than the “warm” years of the past: tracking global temperatures through El Niño and La Niña” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/global-temperatures-el-nino-la-nina' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-global-temperatures-el-nino-la-nina,

author = {Veronika Samborska and Hannah Ritchie},

title = {“Cool” years are now hotter than the “warm” years of the past: tracking global temperatures through El Niño and La Niña},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/global-temperatures-el-nino-la-nina}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.